Barcelona has a long history of housing movements and challenges. Some projects are attempting to alter the narrative surrounding the housing crisis. Visiting these projects was invaluable.

As part of the third general meeting of PREFIGURE, consortium members visited two alternative housing projects in Barcelona.

La Borda

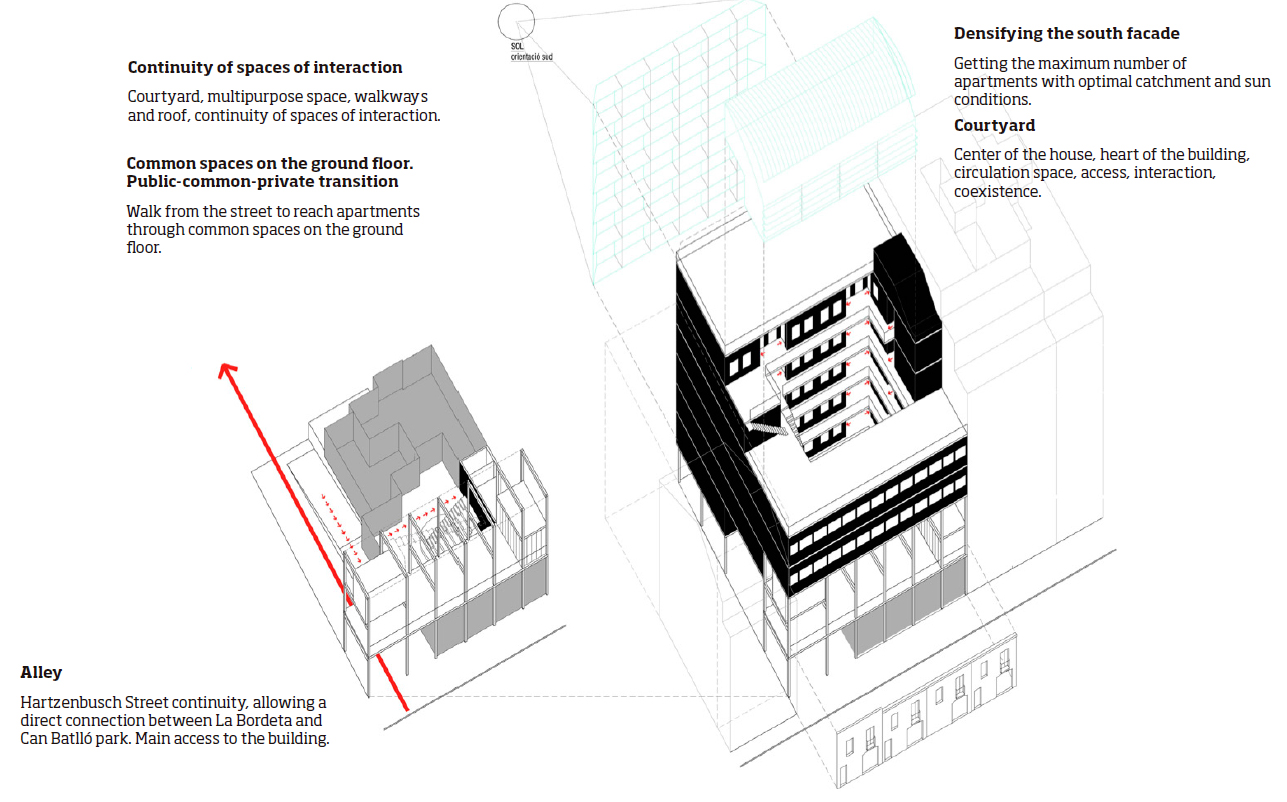

The first one is La Borda, located in the Sants neighbourhood, in the south-west of the city. Accompanied by one of the residents, we toured this impressive 28-apartments building, sat in the communal kitchen, climbed to the top to view the photovoltaic panels installed by the community, and even sneaked into the bright, tidy flat he shares with his child.

La Borda is Barcelona’s first cooperative housing building and was built on public land as a community-driven project. The process began in 2012 as part of the campaign to reclaim Can Batlló, a former industrial site that was converted in the 1970s. A small group of neighbours started implementing a housing cooperative based on the right of use, and involved the cooperative of architects Lacol, who are now also members of the cooperative and residents of the building.

The building has now won many international awards.

In the words of its founders:

At La Borda, we aim to guarantee access to decent, social, affordable, and environmentally sustainable housing, with the aim of fostering new forms of coexistence and building community through interaction between neighbours. We seek a way of living that follows the values of feminist economics and the social and solidarity economy.

But how does this work?

The land is publicly owned, and the building belongs to the community. In 2015, the Barcelona City Council established a leasehold. The property is collectively owned, while use is personal. Residents have cooperative partners status and can live there for life. They cannot rent or sell their property. Decisions are made at General Assembly meetings, and the entire process, including the design, is participatory.

To qualify for accommodation, your yearly gross income must not exceed €45,000. Rent is also fixed yearly. All apartments have a basic structure to which one or two modules can be added to meet individual needs. On the ground floor, the kitchen and dining room are open for joint meals and celebrations, with cooking and cleaning duties divided into shifts. Laundry is also collective and residents can book their slots via an app. Two guest rooms can also be booked for visitors and items for communal use can be purchased for the community. A communal emergency fund is topped up with monthly contributions.

‘What makes the difference’, our guide explained, ‘is that you bring back the figure of the neighbour, that has disappeared in the capitalist economy. We’re not all friends and we don’t all watch movies together every night, but we know we’re always there for one another, if needed’, he remarked.

From the top-floor terrace, we could see the Can Batlló area. The underground parking has been removed and the building now acts as a portal to the park. One of the partners from IDRA explained that what is paradoxical about it is that the private enterprises that are now building luxury housing in the area exploit the proximity to the gardens and facilities of Can Batlló as a selling point to justify higher prices. Food for thought for the next housing struggle?

WikiHousing

The second one is WikiHousing.

WikiHousing is actually one of the project’s prototypes of change, i.e. a prototype for social, political and economic innovations that contribute to affordable housing renovation schemes.

For the visit, we travelled all the way to La Pau, in the east of the city. There, architect David Baró was waiting for outside an industrial warehouse. Inside, we walked through various rooms where young workers were crafting wood items and operating different machineries. When we stopped, the remains of the original structure of WikiHousing, which is currently being dismantled in order be moved and rebuilt – were in front of us.

WikiHousing is a participatory initiative that provides affordable, sustainable public housing through co-design and community involvement.

As in many other European cities, gentrification in Barcelona has come at a high cost to its residents. Compared to the rest of Europe, only 1.5% of houses in the city are affordable. In Vienna, David explained, this figure is over 50%. For young people, living in the city centre is now almost impossible. Yet, there are still empty plots of land that could be used for affordable housing.

To address this issue and help the younger generation in particular, David and his colleague David Juárez have devised a new project combining technological innovation — through sustainable construction materials and methods, as well as modular design — with participatory governance. This will engage future residents in the decision-making and collective management of the building process, thereby increasing the supply of affordable housing.

But how does this work?

Wikihousing uses lightweight balloon frame construction and modular design.

Wood is used as the primary construction material, combined with prefabricated components, to create lightweight, sustainable structures. Not only does wood offer natural durability and thermal insulation, it also significantly reduces the water and energy consumption typically associated with the transportation, manufacturing and installation of conventional building materials. Offsite construction, on the other hand, reduces hazards and has a lower carbon footprint in one of the most dangerous and polluting sectors.

Wikihousing also promotes a ‘do it with others‘ approach to urban design. Over 100 young people were involved in the construction process. By participating, they could develop new skills and even earn a diploma in sustainable construction, which is a growing field. Moreover, construction of the structure only takes a few months rather than several years. These modules can then be dismantled and reassembled in what they called ‘opportunity gaps’: empty plots of land in city centres or on top of existing buildings.

After presenting WikiHousing as a project proposal to the city’s BIT Habitat Foundation and winning the competition, David and David were indeed granted a plot of land owned by the municipality for the project’s development in the Poble-sec neighbourhood. It will be ready for the first residents in October. It is hoped that many more will follow.